Sabre de Lanciers Rouges de la Garde Impériale (Red Lancers)

Jun 27, 2023 20:23:29 GMT

Post by jack88 on Jun 27, 2023 20:23:29 GMT

Sabre de Lanciers Rouges de la Garde Impériale (Saber of the Red Lancers of the Imperial Guard)

After recovering some stragglers, on 20 January 1813, the Red Lancers numbered 42 officers and 244 troopers.

Red Lancer at the Crossing of the Beresina, 1812 by Jules Rigo

After the disaster of Russia, the Red Lancers would lose their distinct Dutchness. Napoleon ordered the Red Lancers to be replenished to 2,000 strong. The officer core and NCOs would retain their experienced Dutch heritage, but young French recruits, mainly from Paris, mounted and equipped by the city, filled the trooper slots as Young Guard. [15] The unit would have five new squadrons added to it for a total of ten. The old squadrons from Russia gained Old Guard status, while the more recent were anointed Young Guard. When Napoleon began his campaign in April 1813, the unit comprised 844 lances, with another 727 on the way. Despite being full of inexperienced young troopers, the Red Lancers would distinguish themselves and restore their position in the Imperial Guard in the 1813/14 campaigns. [16]

Red Lancer by myself.

In the space of a few months, Napoleon did the impossible. He raised an enormous army for the War of the Sixth Coalition. Despite having numbers, he desperately lacked cavalry due to a shortage of horses, which led to the overuse of his guard cavalry. In quick succession, the Red Lancers proved their worth in multiple battles. On 22 May at Reichenbach, they distinguished themselves against their old Cossack foe, defeating a force many times their size at the cost of 197 men. A battle described in detail by Chlapowski,

"We continued at a walk for another three hundred paces, and I instructed both squadrons to go hell for leather as soon as I sounded the charge. They were not to lower their lances, however, but should point them at the enemy's faces. We got so close to the enemy line that we could hear the voices of their officers, reassuring the soldiers with the word: "Szutka!" [It's a ruse]. We were perhaps two hundred paces away when I ordered, "Charge!" and in the blinking of an eye we were upon them. Captain Jankowski was on my right and Lieutenant Gielgud was on my left. The latter's horse had just forced is way among the dragoons when one of their officers stabbed him in his stomach and he was unhorsed (he died several weeks later)."

"The melee lasted but a few seconds. From the moment we struck, the enemy fell into confusion and began to retreat, even including the ulans who had no foe to their front. I did not see how many men fell because I had passed through their line so quickly. My squadrons had themselves become disordered and individuals were chasing after those of the enemy whose horses were weakest, and ordering them to dismount. But shortly I saw a second enemy line approaching, all of them ulans. I stopped my horse, and had only begun to restore order to the ranks when this line began a charge. I was obliged to reform as best I could and order, "Forward! March!" otherwise they would have caught us stationary, which you should never let the enemy do. Indeed, we had just charged and beaten twice our number of dragoons and ulans because they had received our charge at the halt. We had not even noticed the point blank carbine fire of the first enemy line, as this kind of pot-shotting has no effect on veteran troopers. So anyway, in response to the charge of the second line I ordered, "March!" and then, very quickly, "Charge!"

"As they charged, the Russian ulans lost some of their dressing, but they still came on and broke into our line. They outnumbered us, and we should certainly have been beaten if Jerzmanowski had not come up with our second pair of seconds. He was the very best field officer in the regiment, by the most experienced and with a fine, cool judgement. At just the right moment he struck the enemy from our left flank, having come up close at a walk to save energy for his charge. One or two of their wounded were crying out in Polish. This upset me greatly. One of them was still brandishing his sword and refusing to surrender, until one of our troopers said, "Comrade, we're Poles like you." At that he dropped his sword instantly. He must have been told that although dressed like Poles, we were in fact Frenchmen."

"At the very moment the enemy had charged us, an old bearded cossack had appeared from nowhere beside me. He was on foot, and grabbed the left side of my horse's bridle as he aimed his pistol at me. Meanwhile an ulan officer had arrived and was going for me with his sabre. I parried this attack, and just as the cossack was ready to fire, he fell, run through by the lance of chevauleger Jaworski, who received the cross [of the Legion of Honor] for saving my life." [17]

After Reichenbach, they successfully charged the Austrian Corps of General Gyulai at the Battle of Dresden. Then, on 16 September, a detachment of only a hundred lancers routed three Russian battalions and captured six guns. At Leipzig, they were held in reserve but suffered enormous casualties from artillery fire. By the end of the 1813 campaign, they had suffered fifty percent casualties but had succeeded enormously in every action they fought. A nationalist revolt in Holland caused loyalty problems, and Napoleon wisely sent Frenchmen in the unit to suppress the uprising. On 18 December 1813, the Red Lancers numbered 103 officers, 2204 lancers, and 1251 horses. [18]

The 1814 campaign ended in ultimate failure. Napoleon could not defeat so many enemies despite conducting a brilliant defensive campaign. Fighting alongside the Poles again, the Red Lancers repeatedly smashed the Prussian cavalry at St Dizier, La Rothiere, and Champaubert. General Sebastiani "reported to Napoleon that in twenty years' cavalry soldiering he had never seen a more brilliant charge" at St Dizier, which captured many guns and Russian dragoons with minor losses. [19] St Dizier was their last battle of the campaign, but the unit would survive the restoration and return to the tri-color banner once more for Waterloo.

General Colbert at Waterloo by Alphonse Lalauze, note his arm in a sling after being shot at Quatre Bas

Upon Napoleon's departure from Elba, the Red Lancers faced a difficult path to return to the capital, causing their delay, which didn't go unnoticed by Napoleon. When asked why he was so late, Colbert responded, "Sire, not as late as Your Majesty - I have been waiting for you for a year" — words that would cost Colbert dearly after The Hundred Days during the Second Restoration after being published in a newspaper. With the return, there would be only one lancer regiment, incorporating one stubborn squadron of Poles who refused to leave Napoleon's side and mainly Frenchmen that now comprised the unit. However, some of the original Dutch survived. As of 1 June 1815, the Lancers had 63 officers, 1,193 troopers, and 952 horses. Ultimately, the Red Lancers would face the same failure as all other French cavalry units at Waterloo. They charged the British squares five times in vain, unable to break a single formation, resorting to throwing their lances like javelins. The Second Restoration would see them disbanded, but their legacy would live on in the new Dutch Republic, as the unit would be imitated and even populated by many of the old veterans. The Red Lancers proved the multi-national character of the Grand Armée, emulating a Polish unit down to their uniforms and fighting style whilst serving in the prestigious Garde Imperialé. Their rocky start would be reversed in the campaigns of 1813-4, gaining them well-deserved notoriety. [20]

This sword sits at the pinnacle of desirability for collectors, instantly elevating a collection. Simplistic in design, it resembles other light cavalry sabers of the revolution but holds value through the men who carried it. In design, the saber underwent only minor changes in its fifteen years of service, shifting from the first model depicted below on the right to the 3rd model on the left; notice the minor variations of the hilt.

![]()

My saber is an amalgamation of 2nd and 3rd model pieces. The blade signature Manufacture Imperial de Klingenthal Coulaux Freres predates adding dates in the signature, which lasted until 1810. Additionally, the blade was stamped by inspector Nicolas Cherrer who spent just one-year inspecting blades—1807, giving the blade a precise date. Mouton (1798-1809) stamped as the controller. However, Jean Cazamajou, a reviser from 1803-1806 and 1809-1811, stamped the hilt, which does not align with the 1807 blade date.

The LF91 is what makes this sword special. When searching for other marked versions of this saber, I found the following markings:

- " L29 " on clevis. Hit with a tool set . (2nd Model)

- " L45 " on clevis. Hit with a tool set . (Impossible to see the punches)

- " LF 60 " on the tail of the cap. Hit without a toolset. (Dutch Army Museum)

- " LF9I. " on the tail of the cap. Hit without a tool set. (1809-10)

- " LC-20- " on clevis. Hit without a tool set. (1809-10)

- " 2RLB " on cap tail + " 2RLG" on screed. Struck without a set of tools. (Impossible to see the punches)

- " 2RLG " on tail of cap. Struck without set of tools. (1811)

- " 2RLGI9 " on tail of cap. Struck without set of tools. (1811)

- " 2RLH " on yoke + cap tail? Set of tools? (Impossible to see the hallmarks)

Collectors commonly attribute the 2RL to the Red Lancers, but "L" marked blades have yet to be attributed to a unit. However, no other unit using this saber has been demonstrated to inscribe their sabers. Additionally, the "L" by poinçon dates coincide with the arrival of the Dutch Royal Guard to Versaille. At this time, many Dutchmen became light cavalry and needed to be rearmed with this saber. We'll never know whether the "L" stands for Lancier, Lodewijk, or Liijfgarde, but this is enough evidence to attribute these swords to the 2nd Lancers. The Dutch Army Museum is currently indexing its items, and I am in contact with them about this; we'll see what they say. Therefore, the shift in saber marking to 2RL began in 1811 by poinçons. The subsequent letter stands for company, followed by trooper number.

Sword Stats:

The sword weighs 2.2 lbs

33.5" blade

7/16"/.43" thick at the hilt

1.5" wide at the hilt

39.5" in entirety

Point of balance 5" from hilt

What surprised me about this sword is its size. I thought it would be a smaller sword by pictures, but its one of my largest sabers for being a light cavalry sword. This sword has seen the wars, the evidence is in its hard used scabbard and hilt. Furthermore, this sword retains an edge, and has many small nicks along that edge from use.

Now I do conclude that it is unlikely the sword saw Russia, as few of those men returned, but the Red Lancers had detachments left behind, and several depots as well. I do imagine this sword saw the campaigns of 1813-14, which would have put it in the hands of a veteran, as many of the new Parisian recruits in 1813 were equipped with the AN XI. It is truly a workhorse, a very solidly built blade, and its elegance comes from its quality rather than appearance, though even by appearance it outclasses the general trooper sword.

Hope you've all enjoyed the long read!

[1] Ronald Pawly, The Red Lancers (Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press Ltd, 1998), 45; Dezydery Chlapowski, Memoirs of a Polish Lancer, trans. Tim Simmons (Chicago, IL: The Emperor's Press, 1992), 123.

[2] Jean Lhoste and Patrick Resek, Les Sabres: Portés par L'Armée Française (France: Editions du Portail, 2001), 184

[3] Ronald Pawly, Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2007), 6, 21-22.

[4] Ronald Pawly, Napoleon's Red Lancers (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2003) 5.

[5] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 12-13.

[6] Pawly, Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard, 6-7.

[7] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 13-16.

[8] Pawly, Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard, 3.

[9] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 25, 31

[10] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 31-35

[11] Chlapowski, Memoirs of a Polish Lancer, 123.

[12] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 42.

[13] Chlapowski, Memoirs of a Polish Lancer, 123.

[14] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 41, 52, 55.

[15] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 54-55.

[16] Pawly, Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard, 20.

[17] Chlapowski, Memoirs of a Polish Lancer, 143-145.

[18] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 55-70.

[19] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 73-75, 79.

[20] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 103-108.

Lanciers Rouges de la Garde Impériale by Alphonse Lalauze

"Come on then, come on, dandies of Paris!" A Cossack officer shouted. The Red Lancers lined the edge of the woods, eyes on the lone man waving his sword before them. He spurred his horse on, shifting direction back to his lines as a detachment of Poles pursued him. Since the early morning, the Cossacks lining the woods increased from hundreds to thousands in an ever-growing mass of mismatched uniforms and wild-looking men. General Baron Edouard Colbert de Chabanais, the leader of the surviving Red and Polish Lancers of the Guard, now less than half what had entered Russia, pulled his men back, thickening their lines to give a false impression of strength. By 25 October 1812, the retreat from Moscow had begun, and the Lancers of the Guard bivouacked near the village of Oevarofskoie, guarding supply lines against constant Cossack raids. Colbert surveyed his 1,000 men, contrasting them to the three or four thousand Cossacks that lined the woods. By 2 pm, the situation had become untenable, and he ordered a quick withdrawal, barking orders to his nearby officers. Sensing their opportunity, hundreds of Cossacks charged forward, closing the distance with a forward-positioned skirmishing unit. Carbines rang out in the frigid air as the Cossacks quickly enveloped the forty-eight Red Lancers of Captain Schneither. Cursing, Colbert ordered the 2nd Squadron to charge and open a path to the cut-off men gesturing with his sword. Shouts began to fill the edge of the wood line. Steel rang on steel, blades flashed, horses shrieked as riders toppled to the ground—more and more Cossacks piled into the melée, trapping the rescue squadron. Lance to lance, men danced their horses thrusting at one another, some discarding their lances in favor of their sabers as the horses became trapped against one another. In desperation, Colbert gestured with his sword from side to side, drawing a line for his two remaining squadrons to form up on him. He hardly allowed the men to get into position before he began to trot forward. "Sound the charge!" he called to the Trumpet Major. A hundred lances snapped down as the Dutchmen slammed into the side of the Cossacks. Lances shattered as they pierced flesh and bone, sending men and horses to the ground. The Cossacks began to flee, turning and firing ancient-looking firearms, sending wild shots throughout the mass of men. The Cossacks reached the safety of the woods as ten times their number began to form, being driven forward by their officers. "Left about turn by fours!" The Red Lancers disengaged and started a hasty withdrawal as the Cossacks pursued. After thirty minutes, the Cossacks relented, shouting something indistinguishable in the distance. A grizzled Polish Lancer turned to the red uniformed men, "Bravo Dutchmen!" This short skirmish had cost the unit dearly; between twenty-four and a hundred lancers lay dead on the edge of the woods, with many more wounded. (Ronald Pawly 24, Chlapowski "over 100") Despite leaving the field to the enemy, the fight outside Oevarofskoie was the Red Lancer's first real engagement. It encapsulated their harrowing experience in Russia—continual Cossack ambushes, misery, and death. [1]

PICTURE

The trumpet banner found next to the body of Trumpet-Major Kauffman at the Battle of Reichenbach May 1813—picture by Ronald Pawly.

Hello everyone! Today I will give you a glimpse of a project I've begun working on, which will eventually become a book. I plan to discuss famous Napoleonic units and their swords in popular history, an easy read from the academic stuff I publish elsewhere.

Without further ado, I would like to discuss the newfound crown of my collection, a true rarity in superb untampered condition. Additionally, I will give an overview of the famous unit that wielded this weapon, some first-hand accounts, and why this piece is so unique. The model is commonly known as the Sabre Chasseurs à Cheval de La Garde Impériale or saber of the Imperial Guard Chasseurs. It was developed in 1800, coinciding with the creation of a Consular Guard unit of Chasseurs à Cheval (Hunters on horseback). Over fifteen years, Klingenthal and Versailles made approximately 7,000 copies of this sword; however, one can only guess how many survive today. [2]

My saber of the Red Lancers

In 1804 Napoleon crowned himself Emperor and transitioned his Consular Guard into the famed Imperial Guard. At first, only the Chasseurs and Mounted Artillery of the Guard carried this model. In 1807, Napoleon created the Chevau-Légers Polonais de la Garde (Polish Light Horses of the Guard), which transitioned in 1809 to become a lancers unit and equipped with this model. [3]

Elba Squadron of the 1st Light Horse Regiment Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard by Jan Chelminski

The Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard became unequivocally one of the most elite units of the Napoleonic Wars. While I'd love to devote an entire article to them, they are not our topic for today. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_Light_Cavalry_Lancers_Regiment_of_the_Imperial_Guard_(Polish)

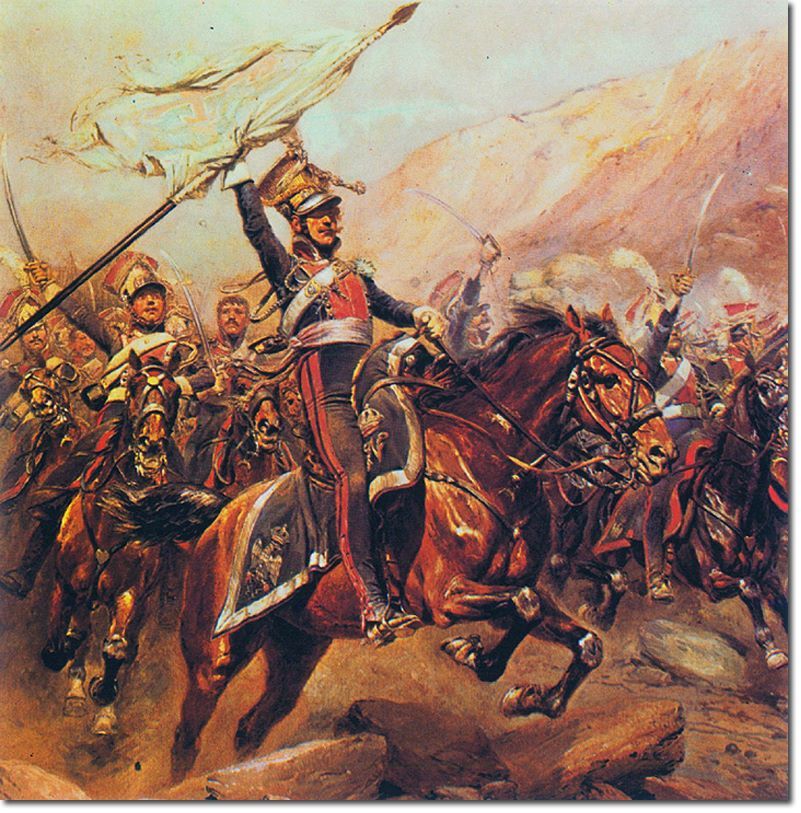

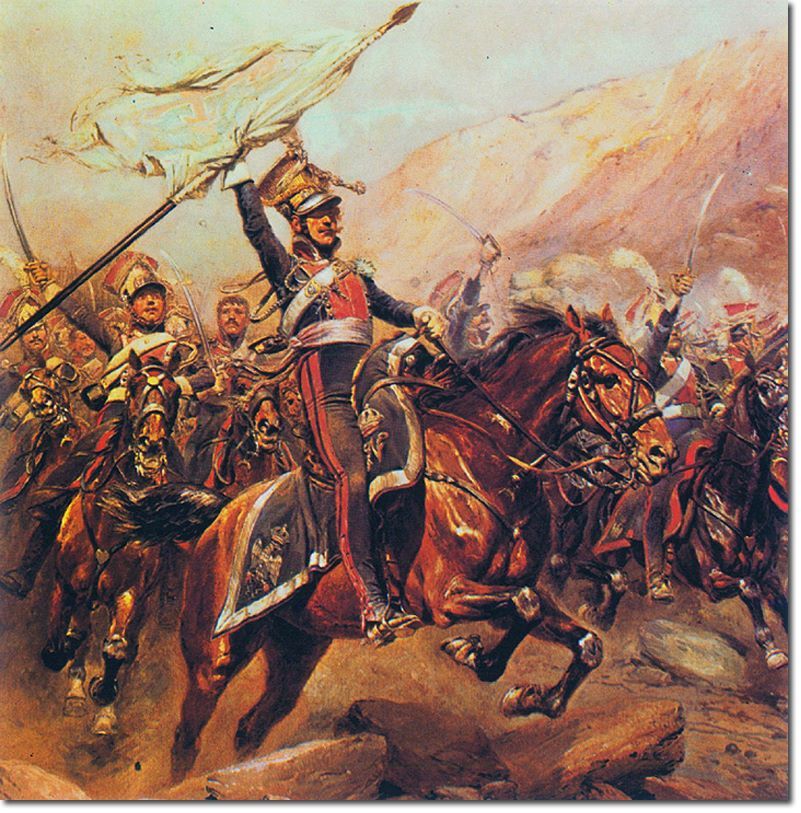

Wincenty Krasinski at the Somosierra Pass by Horace Vernet

Guard of Louis, unknown artist.

Displeased with Louis disregarding Napoleon's Continental System, Napoleon annexed Holland on 9 July 1810 to the Empire. Imperial France absorbed the 27,000-strong Dutch military, and by decree of 10 July, Napoleon brought Louis' guard into the Imperial Guard. The unit arrived in Versaille on 10 August 1810 and famously drank too much wine with the other guard units (the Dutchmen were used to beer), causing them to drunkenly generate mayhem in the town. The results of a wild night in the town saw some velites of the guard blamed for misconduct and promptly sent to the Spanish front. [4]

Hussars and Cuirassiers of the Dutch Royal Guard

The newfound unit would eventually incorporate the Hussars and Cuirassiers of the Dutch Royal Guard and, by merit, the Dutch 3rd Hussars fighting in Spain to bring them up to the required strength. [5] On 13 September, by decree, the Dutchmen transitioned from hussar to lancer, becoming the 2e régiment de chevau-légers lanciers de la Garde impériale (2nd Regiment of Light Horse Lancers of the Imperial Guard), and on "27 November Lt AdjMaj Fallot and eight NCOs went to the Polish Lancers' barracks at Chantilly for a month's drilling in how to manipulate the lance, later returning to Versailles to pass on their knowledge to the rest of the regiment." [6] Additionally, the unit had 48 Germans; however, Napoleon, by decree, mandated the Dutchness of the 2nd Lancers. But after realizing the unnecessary loss, he redefined what it meant to be Dutch, allowing many Germans to stay.

Czapka of the 2nd Lancers

For new uniforms, the 2nd Lancers adopted the 1st Lancer's traditional Polish uniforms but inverted the blue and red, leaving red as the primary color. [7] These beautiful new uniforms dazzled the French public and quickly earned the nickname "Red Lancers," which became commonly used and even went into official unit documents from 1813 onward. [8]

Red Lancer on Parade by Hoynck van Papendrecht

![]()

The Red Lancers crossed the Nieman on 24 June 1812, leading the enormous Grand Armée in the vanguard, spearheading its way through Russia. Like all of the Grand Armée, the Dutchmen suffered heavily from sickness during the advance, losing nearly 400 effective troopers. Furthermore, inexperienced officers caused irrevocable damage. On 27 July, Uhlans surprised and captured forty-eight of them in a farmhouse in Babinovitz while the party was foraging, which gave the Russians a sense of superiority over "the red ones." From 14 August onwards, the Polish Guard Lancers joined General Colbert, bringing a combined total back to nearly 1,000 lances. The Cossacks "seemed insultingly eager to come to blows (perhaps as a result of their easy victory in the fight at Babinovitz." Reportedly the Cossacks would later single out their red uniforms—"A red one! Catch him!" Colbert played on this overeagerness, having the Poles and Dutch switch uniforms, giving the Cossacks a nasty surprise as they engaged with the Old Guard unit. [10] According to Colonel Chlapowski of the Polish Lancers, the Cossacks recognized the Polish riding style, causing them to flee crying, "Lachy! Lachy! [Poles! Poles!]" [11] The Cossacks and Poles had fought many wars against one another, reaching back into the 17th century.

![]()

Crossing the Niemen River by Jan Van Chelminski

The combined Guard Lancer unit took no part in the unimaginative slaughter at Borodino, sitting in reserve for the duration of the battle. Afterward, it resumed its scouting duties, only entering Moscow after it burned.

Captain Calkoen wrote to his father on 5 October, "We have been detached from the guard and are involved daily with the Cossacks, who are doing us a lot of harm. Alerts are frequent. The Cossacks are not brave but they are very skilled at skirmishing, and they always outnumber us when they allow themselves be approached. They are strong because they know the tricks of laying ambushes. They are armed with lances." [12]

On 25 October, the engagement at Oevarofskoie occurred as described above, which caused Chlapowski to write,

"General Colbert ordered my squadrons to return to the brigade and left a squadron of Dutch lancers under a captain in our place. The cossacks noticed the change immediately and attacked again, surrounding the Dutchmen on three sides. Seeing this, General Colbert ordered the whole brigade to charge. The cossacks retired to the tree line but were joined there by ten times their number. Our horses were tired out by their long charge and the cossacks pressed in on us from the front and sides. We lost twenty men and the Dutch lost over a hundred. This was the fault of General Colbert, who over-reacted to the threat to an isolated squadron by hurling everything he had at the enemy. We could have avoided suffering losses if he had charged with only a few squadrons and followed up with the rest of the brigade at a slow and orderly pace. You should never engage your whole strength at once, especially when dealing with cossacks. This was the worst loss we suffered during the entire Russian campaign. We would have lost far more men if the troopers had not been experienced soldiers capable of defending themselves in single combat... The Dutchmen were less experienced than our men and did not know how to handle cossacks. Every time they were in the rearguard they would lose a few men, and the cossacks were becoming increasingly bold in attacking them." [13] Pawly makes no mention of the errant charge, and in fact, Colbert was a very experienced commander, having fought in Spain. Chlapowski had scant respect for the Dutchmen in Russia and strangely never mentioned them again despite a massive change in performance in the later campaigns.

Polish Lancers of the Guard

Forced to retreat, Napoleon left Moscow on 19 November, at which time the unit was down to only 300 fit horses. The retreat from Moscow to Smolensk was an unparalleled disaster. The Grand Armée dwindled from 95,000 to 42,000 men on the march. On 13 December, the lancers crossed out of Russia with a mounted strength of 20 officers, 40 troopers, and about 150 men on foot. Furthermore, the original 1,000 lancers had been reinforced by 401 men throughout the campaign, meaning even more devastating losses. A letter from Sergeant-Major Schreiber to the family of the deceased Colonel van Hasselt's family stated the losses in detail,

"This morning we have received the sad news from the Grande Armee... Of the 56 officers who left form here, 32 are fit for service. The others have been killed, made prisoner, are sick, or have frostbitten feet and hands. Of the 1,090 NCOs and lancers, 191 have been killed by the enemy, 595 died of cold or hardship; and for the horses, of 1,122 only 24 remain fit for service." [14]

![]()

A Polish Lancer fighting a Cossack

"Come on then, come on, dandies of Paris!" A Cossack officer shouted. The Red Lancers lined the edge of the woods, eyes on the lone man waving his sword before them. He spurred his horse on, shifting direction back to his lines as a detachment of Poles pursued him. Since the early morning, the Cossacks lining the woods increased from hundreds to thousands in an ever-growing mass of mismatched uniforms and wild-looking men. General Baron Edouard Colbert de Chabanais, the leader of the surviving Red and Polish Lancers of the Guard, now less than half what had entered Russia, pulled his men back, thickening their lines to give a false impression of strength. By 25 October 1812, the retreat from Moscow had begun, and the Lancers of the Guard bivouacked near the village of Oevarofskoie, guarding supply lines against constant Cossack raids. Colbert surveyed his 1,000 men, contrasting them to the three or four thousand Cossacks that lined the woods. By 2 pm, the situation had become untenable, and he ordered a quick withdrawal, barking orders to his nearby officers. Sensing their opportunity, hundreds of Cossacks charged forward, closing the distance with a forward-positioned skirmishing unit. Carbines rang out in the frigid air as the Cossacks quickly enveloped the forty-eight Red Lancers of Captain Schneither. Cursing, Colbert ordered the 2nd Squadron to charge and open a path to the cut-off men gesturing with his sword. Shouts began to fill the edge of the wood line. Steel rang on steel, blades flashed, horses shrieked as riders toppled to the ground—more and more Cossacks piled into the melée, trapping the rescue squadron. Lance to lance, men danced their horses thrusting at one another, some discarding their lances in favor of their sabers as the horses became trapped against one another. In desperation, Colbert gestured with his sword from side to side, drawing a line for his two remaining squadrons to form up on him. He hardly allowed the men to get into position before he began to trot forward. "Sound the charge!" he called to the Trumpet Major. A hundred lances snapped down as the Dutchmen slammed into the side of the Cossacks. Lances shattered as they pierced flesh and bone, sending men and horses to the ground. The Cossacks began to flee, turning and firing ancient-looking firearms, sending wild shots throughout the mass of men. The Cossacks reached the safety of the woods as ten times their number began to form, being driven forward by their officers. "Left about turn by fours!" The Red Lancers disengaged and started a hasty withdrawal as the Cossacks pursued. After thirty minutes, the Cossacks relented, shouting something indistinguishable in the distance. A grizzled Polish Lancer turned to the red uniformed men, "Bravo Dutchmen!" This short skirmish had cost the unit dearly; between twenty-four and a hundred lancers lay dead on the edge of the woods, with many more wounded. (Ronald Pawly 24, Chlapowski "over 100") Despite leaving the field to the enemy, the fight outside Oevarofskoie was the Red Lancer's first real engagement. It encapsulated their harrowing experience in Russia—continual Cossack ambushes, misery, and death. [1]

PICTURE

The trumpet banner found next to the body of Trumpet-Major Kauffman at the Battle of Reichenbach May 1813—picture by Ronald Pawly.

Hello everyone! Today I will give you a glimpse of a project I've begun working on, which will eventually become a book. I plan to discuss famous Napoleonic units and their swords in popular history, an easy read from the academic stuff I publish elsewhere.

Without further ado, I would like to discuss the newfound crown of my collection, a true rarity in superb untampered condition. Additionally, I will give an overview of the famous unit that wielded this weapon, some first-hand accounts, and why this piece is so unique. The model is commonly known as the Sabre Chasseurs à Cheval de La Garde Impériale or saber of the Imperial Guard Chasseurs. It was developed in 1800, coinciding with the creation of a Consular Guard unit of Chasseurs à Cheval (Hunters on horseback). Over fifteen years, Klingenthal and Versailles made approximately 7,000 copies of this sword; however, one can only guess how many survive today. [2]

My saber of the Red Lancers

In 1804 Napoleon crowned himself Emperor and transitioned his Consular Guard into the famed Imperial Guard. At first, only the Chasseurs and Mounted Artillery of the Guard carried this model. In 1807, Napoleon created the Chevau-Légers Polonais de la Garde (Polish Light Horses of the Guard), which transitioned in 1809 to become a lancers unit and equipped with this model. [3]

Elba Squadron of the 1st Light Horse Regiment Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard by Jan Chelminski

The Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard became unequivocally one of the most elite units of the Napoleonic Wars. While I'd love to devote an entire article to them, they are not our topic for today. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_Light_Cavalry_Lancers_Regiment_of_the_Imperial_Guard_(Polish)

Wincenty Krasinski at the Somosierra Pass by Horace Vernet

The Formation of the Red Lancers

In 1806 Napoleon created the Kingdom of Holland out of the Batavian Republic, placing his brother Louis on the throne, who adopted his Dutch name Lodewijk I. Wishing to imitate his brother's guard, Lodewijk created a Hussar Guard regiment, equipping them with the Guard Chassuer model or M1807 to the Dutch.

Guard of Louis, unknown artist.

Displeased with Louis disregarding Napoleon's Continental System, Napoleon annexed Holland on 9 July 1810 to the Empire. Imperial France absorbed the 27,000-strong Dutch military, and by decree of 10 July, Napoleon brought Louis' guard into the Imperial Guard. The unit arrived in Versaille on 10 August 1810 and famously drank too much wine with the other guard units (the Dutchmen were used to beer), causing them to drunkenly generate mayhem in the town. The results of a wild night in the town saw some velites of the guard blamed for misconduct and promptly sent to the Spanish front. [4]

Hussars and Cuirassiers of the Dutch Royal Guard

The newfound unit would eventually incorporate the Hussars and Cuirassiers of the Dutch Royal Guard and, by merit, the Dutch 3rd Hussars fighting in Spain to bring them up to the required strength. [5] On 13 September, by decree, the Dutchmen transitioned from hussar to lancer, becoming the 2e régiment de chevau-légers lanciers de la Garde impériale (2nd Regiment of Light Horse Lancers of the Imperial Guard), and on "27 November Lt AdjMaj Fallot and eight NCOs went to the Polish Lancers' barracks at Chantilly for a month's drilling in how to manipulate the lance, later returning to Versailles to pass on their knowledge to the rest of the regiment." [6] Additionally, the unit had 48 Germans; however, Napoleon, by decree, mandated the Dutchness of the 2nd Lancers. But after realizing the unnecessary loss, he redefined what it meant to be Dutch, allowing many Germans to stay.

Czapka of the 2nd Lancers

For new uniforms, the 2nd Lancers adopted the 1st Lancer's traditional Polish uniforms but inverted the blue and red, leaving red as the primary color. [7] These beautiful new uniforms dazzled the French public and quickly earned the nickname "Red Lancers," which became commonly used and even went into official unit documents from 1813 onward. [8]

Red Lancer on Parade by Hoynck van Papendrecht

Into Russia

By decree of 11 March 1812, the rank and file of the Red Guards became Middle Guard, while the officers retained their Old Guard status. This change caused significant grumbling amongst the other guardsmen, as this untested unit had not properly earned the right to upgrade from the Young Guard in battle. The Red Lancers were filled with veterans from the war in Spain, but many of the officers remained untested, and the lance was a new weapon to them. However, they would soon face the apocalypse of the Imperial French army in Russia and earn their right to the Old Guard. "At the time of departure the Regiment – including the depot and detachments on the march towards Russia – numbered 57 officers, 1,095 lancers and 1,264 horses. They had a detachment of 25 lancers and 25 horses at Marienwerder and a detachment of 210 lancers at Hanover." [9]

The Red Lancers crossed the Nieman on 24 June 1812, leading the enormous Grand Armée in the vanguard, spearheading its way through Russia. Like all of the Grand Armée, the Dutchmen suffered heavily from sickness during the advance, losing nearly 400 effective troopers. Furthermore, inexperienced officers caused irrevocable damage. On 27 July, Uhlans surprised and captured forty-eight of them in a farmhouse in Babinovitz while the party was foraging, which gave the Russians a sense of superiority over "the red ones." From 14 August onwards, the Polish Guard Lancers joined General Colbert, bringing a combined total back to nearly 1,000 lances. The Cossacks "seemed insultingly eager to come to blows (perhaps as a result of their easy victory in the fight at Babinovitz." Reportedly the Cossacks would later single out their red uniforms—"A red one! Catch him!" Colbert played on this overeagerness, having the Poles and Dutch switch uniforms, giving the Cossacks a nasty surprise as they engaged with the Old Guard unit. [10] According to Colonel Chlapowski of the Polish Lancers, the Cossacks recognized the Polish riding style, causing them to flee crying, "Lachy! Lachy! [Poles! Poles!]" [11] The Cossacks and Poles had fought many wars against one another, reaching back into the 17th century.

Crossing the Niemen River by Jan Van Chelminski

The combined Guard Lancer unit took no part in the unimaginative slaughter at Borodino, sitting in reserve for the duration of the battle. Afterward, it resumed its scouting duties, only entering Moscow after it burned.

Captain Calkoen wrote to his father on 5 October, "We have been detached from the guard and are involved daily with the Cossacks, who are doing us a lot of harm. Alerts are frequent. The Cossacks are not brave but they are very skilled at skirmishing, and they always outnumber us when they allow themselves be approached. They are strong because they know the tricks of laying ambushes. They are armed with lances." [12]

On 25 October, the engagement at Oevarofskoie occurred as described above, which caused Chlapowski to write,

"General Colbert ordered my squadrons to return to the brigade and left a squadron of Dutch lancers under a captain in our place. The cossacks noticed the change immediately and attacked again, surrounding the Dutchmen on three sides. Seeing this, General Colbert ordered the whole brigade to charge. The cossacks retired to the tree line but were joined there by ten times their number. Our horses were tired out by their long charge and the cossacks pressed in on us from the front and sides. We lost twenty men and the Dutch lost over a hundred. This was the fault of General Colbert, who over-reacted to the threat to an isolated squadron by hurling everything he had at the enemy. We could have avoided suffering losses if he had charged with only a few squadrons and followed up with the rest of the brigade at a slow and orderly pace. You should never engage your whole strength at once, especially when dealing with cossacks. This was the worst loss we suffered during the entire Russian campaign. We would have lost far more men if the troopers had not been experienced soldiers capable of defending themselves in single combat... The Dutchmen were less experienced than our men and did not know how to handle cossacks. Every time they were in the rearguard they would lose a few men, and the cossacks were becoming increasingly bold in attacking them." [13] Pawly makes no mention of the errant charge, and in fact, Colbert was a very experienced commander, having fought in Spain. Chlapowski had scant respect for the Dutchmen in Russia and strangely never mentioned them again despite a massive change in performance in the later campaigns.

Polish Lancers of the Guard

Forced to retreat, Napoleon left Moscow on 19 November, at which time the unit was down to only 300 fit horses. The retreat from Moscow to Smolensk was an unparalleled disaster. The Grand Armée dwindled from 95,000 to 42,000 men on the march. On 13 December, the lancers crossed out of Russia with a mounted strength of 20 officers, 40 troopers, and about 150 men on foot. Furthermore, the original 1,000 lancers had been reinforced by 401 men throughout the campaign, meaning even more devastating losses. A letter from Sergeant-Major Schreiber to the family of the deceased Colonel van Hasselt's family stated the losses in detail,

"This morning we have received the sad news from the Grande Armee... Of the 56 officers who left form here, 32 are fit for service. The others have been killed, made prisoner, are sick, or have frostbitten feet and hands. Of the 1,090 NCOs and lancers, 191 have been killed by the enemy, 595 died of cold or hardship; and for the horses, of 1,122 only 24 remain fit for service." [14]

A Polish Lancer fighting a Cossack

After recovering some stragglers, on 20 January 1813, the Red Lancers numbered 42 officers and 244 troopers.

Red Lancer at the Crossing of the Beresina, 1812 by Jules Rigo

After the disaster of Russia, the Red Lancers would lose their distinct Dutchness. Napoleon ordered the Red Lancers to be replenished to 2,000 strong. The officer core and NCOs would retain their experienced Dutch heritage, but young French recruits, mainly from Paris, mounted and equipped by the city, filled the trooper slots as Young Guard. [15] The unit would have five new squadrons added to it for a total of ten. The old squadrons from Russia gained Old Guard status, while the more recent were anointed Young Guard. When Napoleon began his campaign in April 1813, the unit comprised 844 lances, with another 727 on the way. Despite being full of inexperienced young troopers, the Red Lancers would distinguish themselves and restore their position in the Imperial Guard in the 1813/14 campaigns. [16]

Red Lancer by myself.

In the space of a few months, Napoleon did the impossible. He raised an enormous army for the War of the Sixth Coalition. Despite having numbers, he desperately lacked cavalry due to a shortage of horses, which led to the overuse of his guard cavalry. In quick succession, the Red Lancers proved their worth in multiple battles. On 22 May at Reichenbach, they distinguished themselves against their old Cossack foe, defeating a force many times their size at the cost of 197 men. A battle described in detail by Chlapowski,

"We continued at a walk for another three hundred paces, and I instructed both squadrons to go hell for leather as soon as I sounded the charge. They were not to lower their lances, however, but should point them at the enemy's faces. We got so close to the enemy line that we could hear the voices of their officers, reassuring the soldiers with the word: "Szutka!" [It's a ruse]. We were perhaps two hundred paces away when I ordered, "Charge!" and in the blinking of an eye we were upon them. Captain Jankowski was on my right and Lieutenant Gielgud was on my left. The latter's horse had just forced is way among the dragoons when one of their officers stabbed him in his stomach and he was unhorsed (he died several weeks later)."

"The melee lasted but a few seconds. From the moment we struck, the enemy fell into confusion and began to retreat, even including the ulans who had no foe to their front. I did not see how many men fell because I had passed through their line so quickly. My squadrons had themselves become disordered and individuals were chasing after those of the enemy whose horses were weakest, and ordering them to dismount. But shortly I saw a second enemy line approaching, all of them ulans. I stopped my horse, and had only begun to restore order to the ranks when this line began a charge. I was obliged to reform as best I could and order, "Forward! March!" otherwise they would have caught us stationary, which you should never let the enemy do. Indeed, we had just charged and beaten twice our number of dragoons and ulans because they had received our charge at the halt. We had not even noticed the point blank carbine fire of the first enemy line, as this kind of pot-shotting has no effect on veteran troopers. So anyway, in response to the charge of the second line I ordered, "March!" and then, very quickly, "Charge!"

"As they charged, the Russian ulans lost some of their dressing, but they still came on and broke into our line. They outnumbered us, and we should certainly have been beaten if Jerzmanowski had not come up with our second pair of seconds. He was the very best field officer in the regiment, by the most experienced and with a fine, cool judgement. At just the right moment he struck the enemy from our left flank, having come up close at a walk to save energy for his charge. One or two of their wounded were crying out in Polish. This upset me greatly. One of them was still brandishing his sword and refusing to surrender, until one of our troopers said, "Comrade, we're Poles like you." At that he dropped his sword instantly. He must have been told that although dressed like Poles, we were in fact Frenchmen."

"At the very moment the enemy had charged us, an old bearded cossack had appeared from nowhere beside me. He was on foot, and grabbed the left side of my horse's bridle as he aimed his pistol at me. Meanwhile an ulan officer had arrived and was going for me with his sabre. I parried this attack, and just as the cossack was ready to fire, he fell, run through by the lance of chevauleger Jaworski, who received the cross [of the Legion of Honor] for saving my life." [17]

After Reichenbach, they successfully charged the Austrian Corps of General Gyulai at the Battle of Dresden. Then, on 16 September, a detachment of only a hundred lancers routed three Russian battalions and captured six guns. At Leipzig, they were held in reserve but suffered enormous casualties from artillery fire. By the end of the 1813 campaign, they had suffered fifty percent casualties but had succeeded enormously in every action they fought. A nationalist revolt in Holland caused loyalty problems, and Napoleon wisely sent Frenchmen in the unit to suppress the uprising. On 18 December 1813, the Red Lancers numbered 103 officers, 2204 lancers, and 1251 horses. [18]

The 1814 campaign ended in ultimate failure. Napoleon could not defeat so many enemies despite conducting a brilliant defensive campaign. Fighting alongside the Poles again, the Red Lancers repeatedly smashed the Prussian cavalry at St Dizier, La Rothiere, and Champaubert. General Sebastiani "reported to Napoleon that in twenty years' cavalry soldiering he had never seen a more brilliant charge" at St Dizier, which captured many guns and Russian dragoons with minor losses. [19] St Dizier was their last battle of the campaign, but the unit would survive the restoration and return to the tri-color banner once more for Waterloo.

General Colbert at Waterloo by Alphonse Lalauze, note his arm in a sling after being shot at Quatre Bas

Upon Napoleon's departure from Elba, the Red Lancers faced a difficult path to return to the capital, causing their delay, which didn't go unnoticed by Napoleon. When asked why he was so late, Colbert responded, "Sire, not as late as Your Majesty - I have been waiting for you for a year" — words that would cost Colbert dearly after The Hundred Days during the Second Restoration after being published in a newspaper. With the return, there would be only one lancer regiment, incorporating one stubborn squadron of Poles who refused to leave Napoleon's side and mainly Frenchmen that now comprised the unit. However, some of the original Dutch survived. As of 1 June 1815, the Lancers had 63 officers, 1,193 troopers, and 952 horses. Ultimately, the Red Lancers would face the same failure as all other French cavalry units at Waterloo. They charged the British squares five times in vain, unable to break a single formation, resorting to throwing their lances like javelins. The Second Restoration would see them disbanded, but their legacy would live on in the new Dutch Republic, as the unit would be imitated and even populated by many of the old veterans. The Red Lancers proved the multi-national character of the Grand Armée, emulating a Polish unit down to their uniforms and fighting style whilst serving in the prestigious Garde Imperialé. Their rocky start would be reversed in the campaigns of 1813-4, gaining them well-deserved notoriety. [20]

A Saber for the Imperial Guard

This sword sits at the pinnacle of desirability for collectors, instantly elevating a collection. Simplistic in design, it resembles other light cavalry sabers of the revolution but holds value through the men who carried it. In design, the saber underwent only minor changes in its fifteen years of service, shifting from the first model depicted below on the right to the 3rd model on the left; notice the minor variations of the hilt.

My saber is an amalgamation of 2nd and 3rd model pieces. The blade signature Manufacture Imperial de Klingenthal Coulaux Freres predates adding dates in the signature, which lasted until 1810. Additionally, the blade was stamped by inspector Nicolas Cherrer who spent just one-year inspecting blades—1807, giving the blade a precise date. Mouton (1798-1809) stamped as the controller. However, Jean Cazamajou, a reviser from 1803-1806 and 1809-1811, stamped the hilt, which does not align with the 1807 blade date.

The LF91 is what makes this sword special. When searching for other marked versions of this saber, I found the following markings:

- " L29 " on clevis. Hit with a tool set . (2nd Model)

- " L45 " on clevis. Hit with a tool set . (Impossible to see the punches)

- " LF 60 " on the tail of the cap. Hit without a toolset. (Dutch Army Museum)

- " LF9I. " on the tail of the cap. Hit without a tool set. (1809-10)

- " LC-20- " on clevis. Hit without a tool set. (1809-10)

- " 2RLB " on cap tail + " 2RLG" on screed. Struck without a set of tools. (Impossible to see the punches)

- " 2RLG " on tail of cap. Struck without set of tools. (1811)

- " 2RLGI9 " on tail of cap. Struck without set of tools. (1811)

- " 2RLH " on yoke + cap tail? Set of tools? (Impossible to see the hallmarks)

Collectors commonly attribute the 2RL to the Red Lancers, but "L" marked blades have yet to be attributed to a unit. However, no other unit using this saber has been demonstrated to inscribe their sabers. Additionally, the "L" by poinçon dates coincide with the arrival of the Dutch Royal Guard to Versaille. At this time, many Dutchmen became light cavalry and needed to be rearmed with this saber. We'll never know whether the "L" stands for Lancier, Lodewijk, or Liijfgarde, but this is enough evidence to attribute these swords to the 2nd Lancers. The Dutch Army Museum is currently indexing its items, and I am in contact with them about this; we'll see what they say. Therefore, the shift in saber marking to 2RL began in 1811 by poinçons. The subsequent letter stands for company, followed by trooper number.

Sword Stats:

The sword weighs 2.2 lbs

33.5" blade

7/16"/.43" thick at the hilt

1.5" wide at the hilt

39.5" in entirety

Point of balance 5" from hilt

What surprised me about this sword is its size. I thought it would be a smaller sword by pictures, but its one of my largest sabers for being a light cavalry sword. This sword has seen the wars, the evidence is in its hard used scabbard and hilt. Furthermore, this sword retains an edge, and has many small nicks along that edge from use.

Now I do conclude that it is unlikely the sword saw Russia, as few of those men returned, but the Red Lancers had detachments left behind, and several depots as well. I do imagine this sword saw the campaigns of 1813-14, which would have put it in the hands of a veteran, as many of the new Parisian recruits in 1813 were equipped with the AN XI. It is truly a workhorse, a very solidly built blade, and its elegance comes from its quality rather than appearance, though even by appearance it outclasses the general trooper sword.

Hope you've all enjoyed the long read!

[1] Ronald Pawly, The Red Lancers (Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press Ltd, 1998), 45; Dezydery Chlapowski, Memoirs of a Polish Lancer, trans. Tim Simmons (Chicago, IL: The Emperor's Press, 1992), 123.

[2] Jean Lhoste and Patrick Resek, Les Sabres: Portés par L'Armée Française (France: Editions du Portail, 2001), 184

[3] Ronald Pawly, Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2007), 6, 21-22.

[4] Ronald Pawly, Napoleon's Red Lancers (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2003) 5.

[5] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 12-13.

[6] Pawly, Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard, 6-7.

[7] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 13-16.

[8] Pawly, Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard, 3.

[9] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 25, 31

[10] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 31-35

[11] Chlapowski, Memoirs of a Polish Lancer, 123.

[12] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 42.

[13] Chlapowski, Memoirs of a Polish Lancer, 123.

[14] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 41, 52, 55.

[15] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 54-55.

[16] Pawly, Napoleon's Polish Lancers of the Imperial Guard, 20.

[17] Chlapowski, Memoirs of a Polish Lancer, 143-145.

[18] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 55-70.

[19] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 73-75, 79.

[20] Pawly, The Red Lancers, 103-108.