Garde de Bataille of the French Dragoons

Jan 5, 2022 20:13:41 GMT

Post by jack88 on Jan 5, 2022 20:13:41 GMT

Good day to all! This will be a lengthy post describing my newest acquisition: a French Officers "Garde de Bataille" or "Battle Guard" sword and of the versatile men that carried them.

The Trophy, Soldier of 4th French Dragoon Regiment with Prussian Flag, 1806

Origins

The word Dragoon finds its origin with a French type of pistol, a blunderbuss (called a dragon) originating with the formation of mounted firearm-equipped troops in the early 17th century. Intended initially as mounted infantry riding to critical points of conflict, their role as cavalry would expand with training and equipment resembling other heavy cavalry units. Dragoons were considered the jack of all trades, able to be deployed in many fashions. On the march, they would screen the army's flanks and be prepared to reinforce the hussars and other light cavalry units to stiffen the forward screen. They were considered "wobbly" horsemen in battle as often derided by hussar units. Receiving both infantry and cavalry training, they became keenly aware of the weaknesses of both.

As First Consul, Napoleon would inherit 20 understrength dragoon regiments. In 1801 every cavalry unit by Consulate order would create an elite company in every regiment to guard the regimental eagle. These "elite" companies would receive an extra pay referred to as the "pay of the grenade." Napoleon would re-equip six cavalerie and three hussar regiments as dragoons. Five years later, in 1804 would see their greatest extent of numbered units at 30 regiments. 1806 in a move to increase the size of his cavalry, instead of creating new regiments, Napoleon would expand every regiment to 5 squadrons. The 5th squadron would remain in the depot as a training squadron. In 1811 foreseeing war with Russia inevitable, Napoleon would convert five into lancer regiments, and by 1815 only 15 regiments would remain.

A dragoon regiment is broken down as follows:

Regiment = 4 squadrons

Squadron = 2 companies

Company = 2 platoons

Platoon = 3 officers and 116 men

"It has been said that the greatest inconvenience resulting from the use of

dragoons consists in the fact of being obliged at one moment to make them

believe infantry squares cannot resist their charges, and the next moment

that a foot soldier is superior to any horseman." - General Jomini

![]()

Dragoons were usually given the last pick of quality in horses, often going without any horse at all. Napoleon had a difficult time keeping his dragoons outfitted with the needed mounts. 1800-1806 he could only keep roughly 3/4 of his dragoons mounted. Before his planned invasion of England, Napoleon formed two divisions of dismounted dragoons. These men were equipped with infantry-style coats, packs, and boots; however, they brought saddles and bridles, intending to mount captured British horses. This idea was dashed in 1805 with the War of the Third Coalition. These leftover men were reorganized into their units, and entire units were dismounted and given artillery park and baggage train guard duty. These men were derided as the "wooden swords" considered unreliable by the rest of the army.

Colonel Elting writes on the dismounted situation: "The assignment was sensible, but troopers caught up in the shuffle remembered that veteran dragoons, who hadn't walked farther in years than the distance from their barracks to the nearest bar, ended up in the dismounted units, while their mounts were assigned to raw recruits. The results were rough on everybody: hospitals filled up with spavined veterans, recruits got saddle sores. Also, J.A. Oyon wrote gleefully, matters turned ugly when mounted and dismounted elements of several regiments bivouacked together. The limping veterans crowded over to check on their old horses and found them neglected, sore-backed, and lame.

Blood flowed freely, if only from rookies' noses."

Even veteran dragoon units had suffered from poor performance with few instances mid-Empire to bolster their status. They proved helpful in the pursuit after Jena but were often sandwiched between cuirassier units to give confidence. Inexperienced dragoons fell prey to Cossack swarm tactics. Still, Cossacks failed to realize on multiple occasions that both cuirassiers and dragoons wore white cloaks and would learn the hard way how to differentiate the two.

In 1808 Napoleon sent 24 dragoon regiments to Spain to gain experience, and the remaining six went to Italy. The six in Italy would be involved in the 1809 campaign and go to Russia in 1812. The future called "dragoons of Spain" would cut their teeth and evolve into a fiercely experienced arm of Napoleon's army. They were often utilized as heavy cavalry given there was only one cuirassier regiment in Spain and were pitted against the more experienced and heavily armed British heavy cavalry. The six long years fighting against guerillas and in the Peninsular War would grind the dragoons down to small effective units. They were commented on as the most effective cavalry units when withdrawn to France in 1814.

A first hand account of a dragoon's bravery in the Peninsular campaign

"One of their videttes, after being posted facing English dragoon, of the 14th or 16th [Light Dragoon Regiment] displayed an instance of individual gallantry, in which the French, to do them justice, were seldom wanting. Waving his long straight sword, the Frenchman rode within 60 yards of our dragoon, and challenged him to single combat. We immediately expected to see our cavalry man engage his opponent, sword in hand. Instead of this, however, he unslung his carbine and fired at the Frenchman, who not a whit dismayed, shouted out so that every one could hear him, "Venez avec la sabre: je suis pret pour Napoleon et la belle France"(Come with the saber: I'm ready for Napoleon and beautiful France). Having vainly endeavored to induce the Englishman to a personal conflict, and after having endured two or three shots from his carbine, the Frenchman rode proudly back to his ground, cheered even by our own men. We were much amused by his gallantry, while we hissed our own dragoon ... " (Costello "The Peninsular and Waterloo Campaigns" pp 66-67)

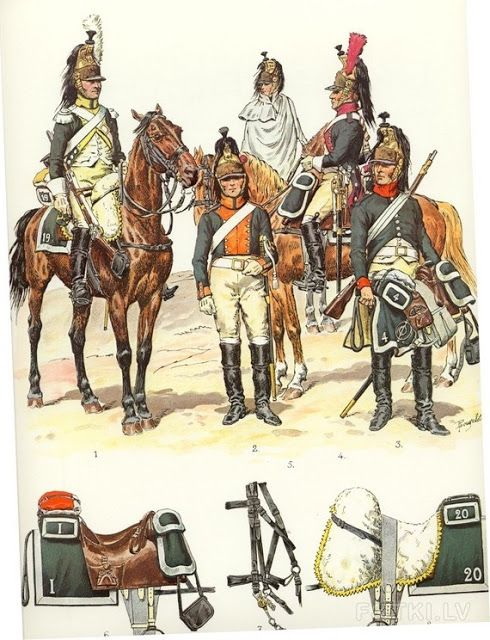

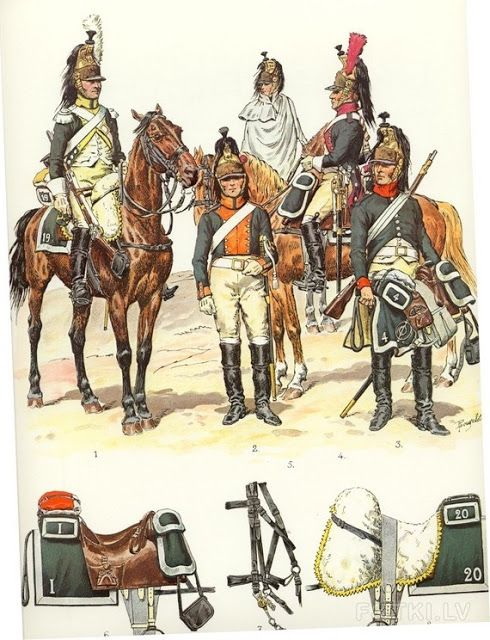

Equipment

French Dragoons would be outfitted with distinctive neo-Grecian bronze helmets with black horsehair. Troopers would cover their helmet with a brown fur turban while officers an imitation leopard skin. They would be issued green coats trimmed in red and given white breeches. Later, when sent to Spain, most would discard their white breeches for brown trousers. They would carry a musket longer than a carbine but shorter than the standard infantry musket.

This "fusil" pictured above resembles the 1766 model. In 1777 the barrel would be shortened to 42 1/2 inches, further reduced to 40 1/2 inches in 1800.

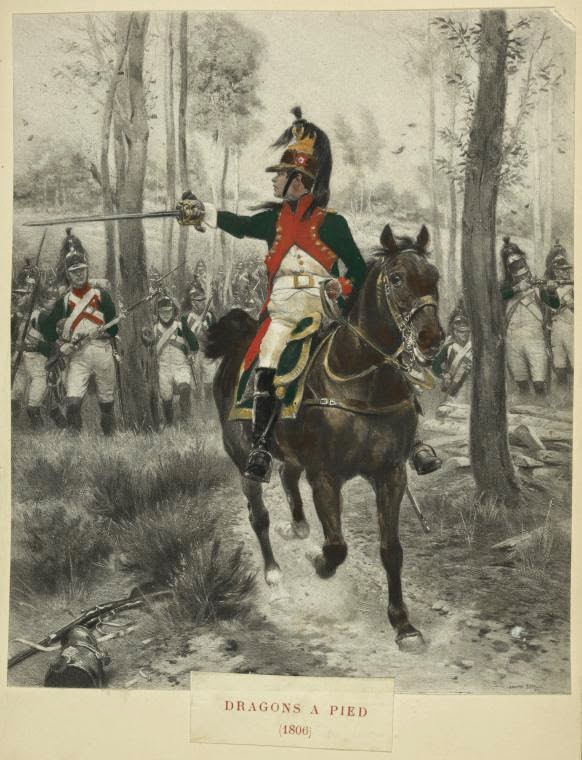

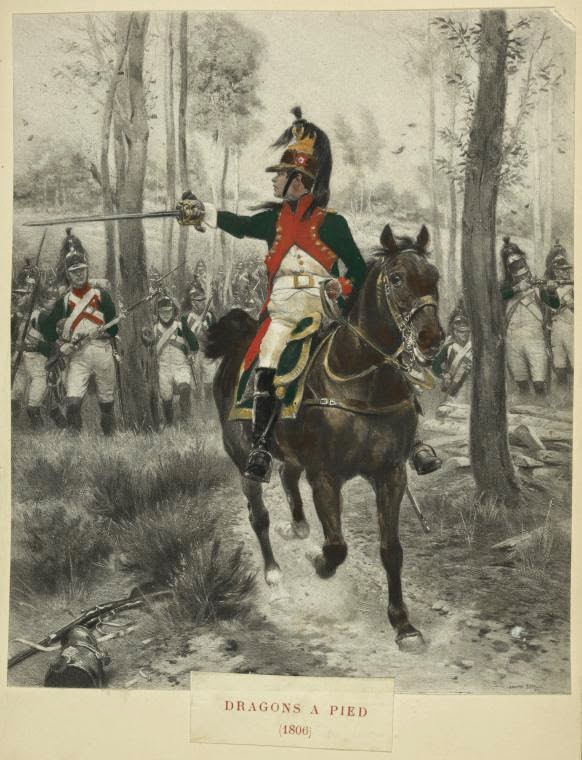

Dragoons on foot in 1806 by Edouard Detaille

Dragoons would receive a sizeable long-bladed pallash similar to their cavalerie counterparts for swords. Take note of dragoon 1770/1776 and eventually dual-purpose AN IV dragoon/cavalerie model pallashes.

In 1784 a cavalry officer model was introduced for both dragoons and cavalerie and had been popularly labeled as a "battle guard" sword. Though no mention of this phrase can be found in historical documents and is likely a label tacked on by collectors. This type of guard would be popular among the heavy cavalry types and see a long service as far as into the 1830s.

The Garde de Bataille

These swords come in many blade configurations and saw some development over time. The blade can either be straight, with a slight curve, or, as the restoration would see, curved enough to be considered a saber. Pommel caps can be circular, octagonal, or customized as the lion pommeled sword below. The release of the AN XI would see the GdB receive the same double fullered blade. Like any period, this being officer's blade saw a wide array of customization regulations be damned.

The scabbards come in several configurations and can be generally dated by the drag. Cavalerie or cuirassier officers would later in mid-empire get AN XI metal scabbards for their GdB's. The blades were often produced domestically in Klingenthal and are signed as such at the base of the blade. Still, many Solingen rose-marked copies are found as well.

My Garde de Bataille

This specific GdB is a mishmash of parts and likely saw long extended service. The scabbard drag is of the original 1784 design.

Specs:

Length in scabbard 42 3/4''

Length out of scabbard 42 1/2"

Blade 37"

POB from hilt 5"

Grip 4"

Blade weight is 2lbs 8.5 oz or 1150g (140g less than the AN XIII!)

The furbisher is poorly stamped as "BRUN," described as a "revolutionary time-period" furbisher by Malvaux. At some point in its service, it suffered a severe blow to the weak side of the asymmetrical guard. I can think of a few occurrences that would cause a severe bend towards the grip, perhaps a fall from a horse at full speed? I'll never know.

There is a distinct line along the point of bend on the guard as well.

At some point in the sword's service, either from the suspected fall or other damage, the sword received a replacement blade. The blade is of AN XI design, with the two fullers stamped with the Solingen rose.

The secondary inspector/furbisher is stamped on both sides of the quillons as "RM." RM is described by L'Hoste as "an unidentified controller, probably from Klingenthal, featured on the quillon of a battle grade saber of the 1784 model." The blade replacement was done poorly, with evidence on both sides of the guard and blade of the vice grip used.

Given the timeframe of the sword's lifecycle, I suspect that this could've been a rushed job in the desperate attempt to rearm the military after the disastrous 1812 Russian campaign. The main head-scratcher with this sword is the spear pointing of the blade. Spear pointing of pallashes was done by regulation in 1816. Still, like the 1816 model sheath, there is evidence of troopers having these modifications at least pre-Waterloo due to captured weapons put on display in various museums. Also, as previously discussed, officers mainly did whatever they pleased regarding weapon regulations. The spear pointing of the GdB is unlike the tip of my AN XIII. The reverse side of the blade has been sharpened at least six inches down the back of the blade.

Further adding to the question is that the sheath in its current configuration works fine, but there is absolutely zero extra room for the old-styled hatchet point. This means the blade was assigned this scabbard having already been spear-pointed, maybe out of necessity? The sheath was intended to fit a flat blade, and the double fullered blade does make it challenging to sheath; however, it draws smoothly.

Worst case scenario of this sword is that it is an assortment of pieces for an old dragoon officer fitted together wanting to reminisce on the old glory days. I find this unlikely the peen show requisite aging and no sign of being ground down for a further rounding. The peen itself is not flat and does retain a roundness to its shape.

Well aged peen.

Bottom line

This is a beautiful battle-made officer's sword. It retains most of its bluing and gilt. It is far more balanced in hand than my AN XIII. I bought it far below value even of it being at risk of being a composite, but I really do not think it is (I'll never know for sure). This sword has been on my list for quite some time and puts me one step closer to completing my Napoleonic French collection.

Thanks for the read!

Cheers!

Sources:

L'Hoste "Les Sabres"

Elting "Swords around a Throne"

www.napolun.com/mirror/web2.airmail.net/napoleon/cavalry_Napoleon.html

napoleonistyka.atspace.com/French_Cavalry.html#_dragoons

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dragoon#France

tweedlandthegentlemansclub.blogspot.com/2021/02/cavalry-of-napoleonic-era-cuirassiers.html

The Trophy, Soldier of 4th French Dragoon Regiment with Prussian Flag, 1806

Origins

The word Dragoon finds its origin with a French type of pistol, a blunderbuss (called a dragon) originating with the formation of mounted firearm-equipped troops in the early 17th century. Intended initially as mounted infantry riding to critical points of conflict, their role as cavalry would expand with training and equipment resembling other heavy cavalry units. Dragoons were considered the jack of all trades, able to be deployed in many fashions. On the march, they would screen the army's flanks and be prepared to reinforce the hussars and other light cavalry units to stiffen the forward screen. They were considered "wobbly" horsemen in battle as often derided by hussar units. Receiving both infantry and cavalry training, they became keenly aware of the weaknesses of both.

As First Consul, Napoleon would inherit 20 understrength dragoon regiments. In 1801 every cavalry unit by Consulate order would create an elite company in every regiment to guard the regimental eagle. These "elite" companies would receive an extra pay referred to as the "pay of the grenade." Napoleon would re-equip six cavalerie and three hussar regiments as dragoons. Five years later, in 1804 would see their greatest extent of numbered units at 30 regiments. 1806 in a move to increase the size of his cavalry, instead of creating new regiments, Napoleon would expand every regiment to 5 squadrons. The 5th squadron would remain in the depot as a training squadron. In 1811 foreseeing war with Russia inevitable, Napoleon would convert five into lancer regiments, and by 1815 only 15 regiments would remain.

A dragoon regiment is broken down as follows:

Regiment = 4 squadrons

Squadron = 2 companies

Company = 2 platoons

Platoon = 3 officers and 116 men

"It has been said that the greatest inconvenience resulting from the use of

dragoons consists in the fact of being obliged at one moment to make them

believe infantry squares cannot resist their charges, and the next moment

that a foot soldier is superior to any horseman." - General Jomini

Dragoons were usually given the last pick of quality in horses, often going without any horse at all. Napoleon had a difficult time keeping his dragoons outfitted with the needed mounts. 1800-1806 he could only keep roughly 3/4 of his dragoons mounted. Before his planned invasion of England, Napoleon formed two divisions of dismounted dragoons. These men were equipped with infantry-style coats, packs, and boots; however, they brought saddles and bridles, intending to mount captured British horses. This idea was dashed in 1805 with the War of the Third Coalition. These leftover men were reorganized into their units, and entire units were dismounted and given artillery park and baggage train guard duty. These men were derided as the "wooden swords" considered unreliable by the rest of the army.

Colonel Elting writes on the dismounted situation: "The assignment was sensible, but troopers caught up in the shuffle remembered that veteran dragoons, who hadn't walked farther in years than the distance from their barracks to the nearest bar, ended up in the dismounted units, while their mounts were assigned to raw recruits. The results were rough on everybody: hospitals filled up with spavined veterans, recruits got saddle sores. Also, J.A. Oyon wrote gleefully, matters turned ugly when mounted and dismounted elements of several regiments bivouacked together. The limping veterans crowded over to check on their old horses and found them neglected, sore-backed, and lame.

Blood flowed freely, if only from rookies' noses."

Even veteran dragoon units had suffered from poor performance with few instances mid-Empire to bolster their status. They proved helpful in the pursuit after Jena but were often sandwiched between cuirassier units to give confidence. Inexperienced dragoons fell prey to Cossack swarm tactics. Still, Cossacks failed to realize on multiple occasions that both cuirassiers and dragoons wore white cloaks and would learn the hard way how to differentiate the two.

In 1808 Napoleon sent 24 dragoon regiments to Spain to gain experience, and the remaining six went to Italy. The six in Italy would be involved in the 1809 campaign and go to Russia in 1812. The future called "dragoons of Spain" would cut their teeth and evolve into a fiercely experienced arm of Napoleon's army. They were often utilized as heavy cavalry given there was only one cuirassier regiment in Spain and were pitted against the more experienced and heavily armed British heavy cavalry. The six long years fighting against guerillas and in the Peninsular War would grind the dragoons down to small effective units. They were commented on as the most effective cavalry units when withdrawn to France in 1814.

A first hand account of a dragoon's bravery in the Peninsular campaign

"One of their videttes, after being posted facing English dragoon, of the 14th or 16th [Light Dragoon Regiment] displayed an instance of individual gallantry, in which the French, to do them justice, were seldom wanting. Waving his long straight sword, the Frenchman rode within 60 yards of our dragoon, and challenged him to single combat. We immediately expected to see our cavalry man engage his opponent, sword in hand. Instead of this, however, he unslung his carbine and fired at the Frenchman, who not a whit dismayed, shouted out so that every one could hear him, "Venez avec la sabre: je suis pret pour Napoleon et la belle France"(Come with the saber: I'm ready for Napoleon and beautiful France). Having vainly endeavored to induce the Englishman to a personal conflict, and after having endured two or three shots from his carbine, the Frenchman rode proudly back to his ground, cheered even by our own men. We were much amused by his gallantry, while we hissed our own dragoon ... " (Costello "The Peninsular and Waterloo Campaigns" pp 66-67)

Equipment

French Dragoons would be outfitted with distinctive neo-Grecian bronze helmets with black horsehair. Troopers would cover their helmet with a brown fur turban while officers an imitation leopard skin. They would be issued green coats trimmed in red and given white breeches. Later, when sent to Spain, most would discard their white breeches for brown trousers. They would carry a musket longer than a carbine but shorter than the standard infantry musket.

This "fusil" pictured above resembles the 1766 model. In 1777 the barrel would be shortened to 42 1/2 inches, further reduced to 40 1/2 inches in 1800.

Dragoons on foot in 1806 by Edouard Detaille

Dragoons would receive a sizeable long-bladed pallash similar to their cavalerie counterparts for swords. Take note of dragoon 1770/1776 and eventually dual-purpose AN IV dragoon/cavalerie model pallashes.

In 1784 a cavalry officer model was introduced for both dragoons and cavalerie and had been popularly labeled as a "battle guard" sword. Though no mention of this phrase can be found in historical documents and is likely a label tacked on by collectors. This type of guard would be popular among the heavy cavalry types and see a long service as far as into the 1830s.

The Garde de Bataille

These swords come in many blade configurations and saw some development over time. The blade can either be straight, with a slight curve, or, as the restoration would see, curved enough to be considered a saber. Pommel caps can be circular, octagonal, or customized as the lion pommeled sword below. The release of the AN XI would see the GdB receive the same double fullered blade. Like any period, this being officer's blade saw a wide array of customization regulations be damned.

The scabbards come in several configurations and can be generally dated by the drag. Cavalerie or cuirassier officers would later in mid-empire get AN XI metal scabbards for their GdB's. The blades were often produced domestically in Klingenthal and are signed as such at the base of the blade. Still, many Solingen rose-marked copies are found as well.

My Garde de Bataille

This specific GdB is a mishmash of parts and likely saw long extended service. The scabbard drag is of the original 1784 design.

Specs:

Length in scabbard 42 3/4''

Length out of scabbard 42 1/2"

Blade 37"

POB from hilt 5"

Grip 4"

Blade weight is 2lbs 8.5 oz or 1150g (140g less than the AN XIII!)

The furbisher is poorly stamped as "BRUN," described as a "revolutionary time-period" furbisher by Malvaux. At some point in its service, it suffered a severe blow to the weak side of the asymmetrical guard. I can think of a few occurrences that would cause a severe bend towards the grip, perhaps a fall from a horse at full speed? I'll never know.

There is a distinct line along the point of bend on the guard as well.

At some point in the sword's service, either from the suspected fall or other damage, the sword received a replacement blade. The blade is of AN XI design, with the two fullers stamped with the Solingen rose.

The secondary inspector/furbisher is stamped on both sides of the quillons as "RM." RM is described by L'Hoste as "an unidentified controller, probably from Klingenthal, featured on the quillon of a battle grade saber of the 1784 model." The blade replacement was done poorly, with evidence on both sides of the guard and blade of the vice grip used.

Given the timeframe of the sword's lifecycle, I suspect that this could've been a rushed job in the desperate attempt to rearm the military after the disastrous 1812 Russian campaign. The main head-scratcher with this sword is the spear pointing of the blade. Spear pointing of pallashes was done by regulation in 1816. Still, like the 1816 model sheath, there is evidence of troopers having these modifications at least pre-Waterloo due to captured weapons put on display in various museums. Also, as previously discussed, officers mainly did whatever they pleased regarding weapon regulations. The spear pointing of the GdB is unlike the tip of my AN XIII. The reverse side of the blade has been sharpened at least six inches down the back of the blade.

Further adding to the question is that the sheath in its current configuration works fine, but there is absolutely zero extra room for the old-styled hatchet point. This means the blade was assigned this scabbard having already been spear-pointed, maybe out of necessity? The sheath was intended to fit a flat blade, and the double fullered blade does make it challenging to sheath; however, it draws smoothly.

Worst case scenario of this sword is that it is an assortment of pieces for an old dragoon officer fitted together wanting to reminisce on the old glory days. I find this unlikely the peen show requisite aging and no sign of being ground down for a further rounding. The peen itself is not flat and does retain a roundness to its shape.

Well aged peen.

Bottom line

This is a beautiful battle-made officer's sword. It retains most of its bluing and gilt. It is far more balanced in hand than my AN XIII. I bought it far below value even of it being at risk of being a composite, but I really do not think it is (I'll never know for sure). This sword has been on my list for quite some time and puts me one step closer to completing my Napoleonic French collection.

Thanks for the read!

Cheers!

Sources:

L'Hoste "Les Sabres"

Elting "Swords around a Throne"

www.napolun.com/mirror/web2.airmail.net/napoleon/cavalry_Napoleon.html

napoleonistyka.atspace.com/French_Cavalry.html#_dragoons

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dragoon#France

tweedlandthegentlemansclub.blogspot.com/2021/02/cavalry-of-napoleonic-era-cuirassiers.html