|

|

Post by larason2 on Mar 12, 2023 21:21:55 GMT

I'd like to try my hand at sand casting, and want to try to make the sword of Goujian. However, details on how it was made are scarce, and there's some contradictions (like Sword of Northshire's site). My best guess is differential casting and carving the mold, but I'm still pretty spotty on the details of those two things, especially how you go about patinating it. I'm pretty familiar with niage, so that will be my default unless I find out more about this casting stuff. I'd like to cut with it, and I don't think that cutting with a casted sword would work out well if I just ground the edge and didn't work harden. Does anyone know a bit more about it, or know where to point me? Thanks!

|

|

|

|

Post by Turok on Mar 23, 2023 6:40:23 GMT

Hi larason2! Maybe you can ask rhema1313 of Rhema Creations. He specializes in ancient Roman weapons, but he has a lot of knowledge with sword making. Neil Burridge is another option to contact, and he focuses a lot on Bronze Age swords.

I wish I could be more helpful but bronze swords aren't my specialty.

|

|

|

|

Post by larason2 on Mar 23, 2023 13:47:29 GMT

Thanks for your reply! I've asked around on other forums, and I think I'm closer to understanding what they did. Ford Hallam at the Nihonto Message board and Alan Longmire at the Bladesmith's forum were very helpful. What I think they did was carve the mold to accommodate metal pieces of different alloys, the 50/50 copper/tin for the blade, and the tin enriched surface cross hatch. Then, they casted as usual. I think they then treated with a sulfurous solution once it was polished to protect the surface, but I'm still looking into that! Thanks for the tips, I'll contact them!

|

|

|

|

Post by zi on Nov 28, 2023 9:11:48 GMT

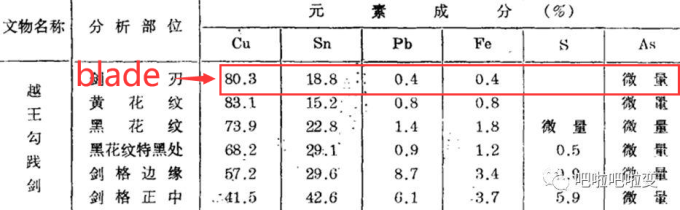

Thanks for your reply! I've asked around on other forums, and I think I'm closer to understanding what they did. Ford Hallam at the Nihonto Message board and Alan Longmire at the Bladesmith's forum were very helpful. What I think they did was carve the mold to accommodate metal pieces of different alloys, the 50/50 copper/tin for the blade, and the tin enriched surface cross hatch. Then, they casted as usual. I think they then treated with a sulfurous solution once it was polished to protect the surface, but I'm still looking into that! Thanks for the tips, I'll contact them! I think…For the Chinese bronze sword (770~256 BC)…Not considering local segregation of Sn element,the tin content is approximately 15% in blade, never exceed 20%....... It may also contain a few lead for liquidity(0%~10%).    |

|

|

|

Post by larason2 on Nov 28, 2023 15:28:51 GMT

Yes, you're right. So, to make it, you have to cast three different alloys. For the blade (spine), it's 83% copper, 15% tin 1% lead and 1% iron. For the blade edge, it's 41% copper, 43% tin, 6% lead, 4% iron, 6% sulfur. For the cross hatch pattern on the blade, 68% copper, 29% tin, 1% lead, 1% iron, 1 % sulfur. The blade edges you cast as a thin strip, and the cross hatch pattern cast as a flat sheet. Then the flat sheet is cut by hand into the diamonds you see on the guojian sword. Then you make the sword mold out of casting sand, and carve out the mold and put into the carved sides of the mold the sheet/strips that you cast before. Then you cast the blade (spine) into the mold. Then the other alloys will be integrated into the blade/spine. This is called "differential casting," and is apparently how a lot of bronze age swords were made.

By the way, thanks for the nice pictures above, that's very helpful! I wasn't able to get the original papers for the research above, and I couldn't find a good picture for how the guard and the blade fit together! The sword shown above doesn't have the cross hatch pattern of the Guojian sword, but I would presume it does have the high tin edge.

|

|

|

|

Post by zi on Nov 29, 2023 2:16:56 GMT

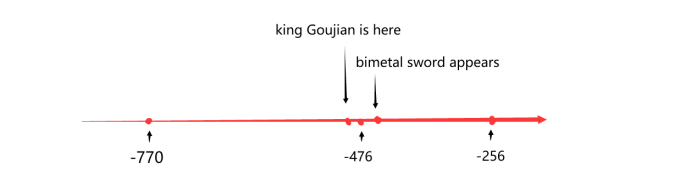

Yes, you're right. So, to make it, you have to cast three different alloys. For the blade (spine), it's 83% copper, 15% tin 1% lead and 1% iron. For the blade edge, it's 41% copper, 43% tin, 6% lead, 4% iron, 6% sulfur. For the cross hatch pattern on the blade, 68% copper, 29% tin, 1% lead, 1% iron, 1 % sulfur. The blade edges you cast as a thin strip, and the cross hatch pattern cast as a flat sheet. Then the flat sheet is cut by hand into the diamonds you see on the guojian sword. Then you make the sword mold out of casting sand, and carve out the mold and put into the carved sides of the mold the sheet/strips that you cast before. Then you cast the blade (spine) into the mold. Then the other alloys will be integrated into the blade/spine. This is called "differential casting," and is apparently how a lot of bronze age swords were made. By the way, thanks for the nice pictures above, that's very helpful! I wasn't able to get the original papers for the research above, and I couldn't find a good picture for how the guard and the blade fit together! The sword shown above doesn't have the cross hatch pattern of the Guojian sword, but I would presume it does have the high tin edge. en……you know……It did happen that the blades were cast from different metals , but the sword of king Goujian was not.  The situation you're talking about is called "bimetal Bronze sword of Warring States”. It looks like this:

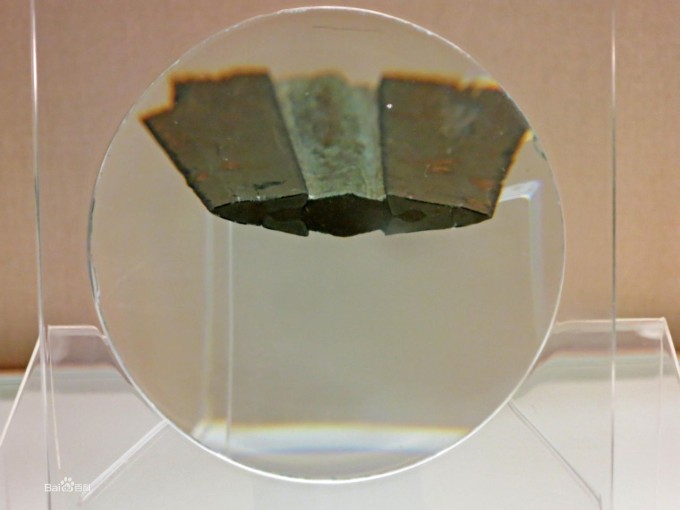

the tin never exceed 20% in bronze of edges except burial object. and the contains less than 10% or even 5% in keel. The table posted before shows the proportion of the main parts of the king Goujian sword. Tin content:18.8% in blade, 15.2%~29.1% in plaid, 29.6%~42.6% in guard。 In addition,let me show you an interesting photo that is very rare on the Internet. The remains of an encient sword grip.  You can clearly see what is the ramie rope wrapped around the wooden part |

|

|

|

Post by larason2 on Nov 29, 2023 3:04:19 GMT

That's interesting, thanks! If differential casting wasn't used, then how did they get all those different tin, lead, iron and sulfur concentrations on the sword? I can't think of any other way to do it. Once you melt copper, any added metals are equally distributed.

Edit: I see where it says 剑格正中, that's referring to the sword guard. On wikipedia, it says that's the sword edge! So clearly a mistranslation there. Still, I think the raised pattern on the sword face must have been differentially casted.

|

|

|

|

Post by zi on Nov 29, 2023 3:17:49 GMT

That's interesting, thanks! If differential casting wasn't used, then how did they get all those different tin, lead, iron and sulfur concentrations on the sword? I can't think of any other way to do it. Once you melt copper, any added metals are equally distributed.

Edit: I see where it says 剑格正中, that's referring to the sword guard. On wikipedia, it says that's the sword edge! So clearly a mistranslation there. Still, I think the raised pattern on the sword face must have been differentially casted.

Because the melting points are different,tin will accumulate in places where it cools quickly (thin areas) .All you need to do is minimize the amount of sanding,save the high tin parts

btw:

The composition of the guard varies greatly, most likely because There's probably a little bit of welding flux left. Geometric pits on the guard, originally inlaid/brazedwith gold and turquoise |

|

|

|

Post by larason2 on Nov 29, 2023 3:32:38 GMT

Ah, that's helpful. Thanks! So they just carved the mold to get the pattern on it then. Given that, I'm guessing the sulfur was also a small amount in the copper, and ended up on the edges as well, or do you know if they used some kind of chemical to patinate the sword?

|

|

|

|

Post by zi on Nov 29, 2023 3:57:19 GMT

Ah, that's helpful. Thanks! So they just carved the mold to get the pattern on it then. Given that, I'm guessing the sulfur was also a small amount in the copper, and ended up on the edges as well, or do you know if they used some kind of chemical to patinate the sword?

I remember that there are two ways to achieve the desired effect.

The physical method is to fill the grooves with additional alloy powder mixed with a flammable adhesive(The traditional Chinese recipe is the liquid from the boiled bletilla tuber) and heat up.then you'll get the plaid you want.

Chemical methods.....Ah!I remember now. High temperature diffusion method by tin amalgam. It is likely that the black color comes not only from tin, but also from additional metallic mercury diffused into the bronze

i think you r right. The new view is that, sulfide doesn't protect bronze any better, may even be easier to make it dull. Sulfur is probably a flaw in early metallurgical techniques that were not good enough. |

|

|

|

Post by larason2 on Nov 29, 2023 21:57:22 GMT

Thanks, that's helpful. I don't have the equipment to safely work with mercury, so I think when I try my hand at this, I'll mix some powdered metal, flour for flux, and water and use that to coat the edges of the mold that I want darkened, and cast all at once. The other alternative is to test different patinators like liver of sulfur and see if I can get something close!

Last summer I practiced casting different alloys, but I didn't have enough sand to cast the swords I wanted. I have a mold I carved of a european bronze age sword, but this winter I hope to also make a mold for the sword of guojian! That picture of the handle is very interesting, almost looks like a Japanese sword with the wrap and the menuki on wood.

|

|

|

|

Post by justanerd on Aug 7, 2024 23:10:16 GMT

HELLO! I'm new! i'd like to open this convo back up. Did some digging around.

There is a story of a black smith named Ou Yezi. He's written in a book called Chinese Mythology by Anne Birrell, who made King Goujian 3 swords in the past. Historians say that its certain that he made the sword of Gouhjian, but alas, no one can know for sure.

Yezi also trained someone else. He had a student.

Gan Jiang and Mo Ye.

I also studied a lot of the common bronze work they did back in the day too. The Yue in 400bc-to around 100ad.

These studies helped me learn a few things, and assume others.

Now, I dont cast bronze, but I was wondering if anyone would like to try a method or 2 that I read up on.

There was said to be trace amounts of AL in the Sword of Goujian, and Nickel too.

I think the Aluminum was introduced by accident, cause there are clay deposits located near the parts of the area that had boaxite and other aluminum in the clays. Kayotin (Spelling) clay is one of them.

is it possible to heat your tin and copper to just melting point, and poor in clay molds without the molds taking damage, and filling all the corners of the molds? Or, do you think the smith carved and cut out the shapes after molding?

If clay molds ARE possible with bronze, how hard is it to accurately shape the bronze from the molds?

If this is possible, do you think the aluminum could have been transferred this way?

Also, the sulfur. in common Japanese sword making, they paint the clay on the edge, this helps with heat treating, and so on.

They said the Sword of Goujian had variable heat treating done too.

The core of the sword had higher copper than the tin, and opposite on the outside.

My theory on this, is that the core was cast, then while still hot, and solid enough to, i think the core was put in a cast, and poured high tin bronze over the core.

I think there were more than one casting of the blade itself.

Is is possible to cast around the core, while the core was still red hot, and have the 2 layers fuse?

If not, they also said the Sword could have been pounded too. Do you think the 2 castings together was then pounded together? There would be needing a flux tho.

If the flux was a clay base, do you think sulfur or aluminum was involved?

Cast the core, high copper, low tin. Dip that in a clay for flux reasons, and then place that core, while still hot, in another casting, good and centered and then pour the other bronze... i would TOTALLY try this, and play with bronze, but I have nothing to do this with. I want to, but I'm a fast food employee with many hopes and dreams. ^-^

|

|

|

|

Post by justanerd on Aug 7, 2024 23:14:08 GMT

also said this.

"According to the historical text Wuyue Chunqiu, King Helü of Wu ordered Gan Jiang and Mo Ye to forge a pair of swords for him in three months.[1] However, the blast furnace failed to melt the metal. Mo Ye suggested that there was insufficient human qi in the furnace so the couple cut their hair and nails and cast them into the furnace, while 300 children helped to blow air into the bellows.[1] In another account, Mo Ye sacrificed herself to increase human qi by throwing herself into the furnace. The desired result was achieved after three years and the two swords were named after the couple."

but idk how true this is.. maybe we need 300 children lol

|

|

|

|

Post by fivesidedpixels on Aug 8, 2024 9:10:43 GMT

HELLO! I'm new! i'd like to open this convo back up. Did some digging around. There is a story of a black smith named Ou Yezi. He's written in a book called Chinese Mythology by Anne Birrell, who made King Goujian 3 swords in the past. Historians say that its certain that he made the sword of Gouhjian, but alas, no one can know for sure. Yezi also trained someone else. He had a student. Gan Jiang and Mo Ye. I also studied a lot of the common bronze work they did back in the day too. The Yue in 400bc-to around 100ad. These studies helped me learn a few things, and assume others. While necroposting is a bit of a faux pas (seen decade-old threads get revived lol), I think you've brought some valuable insight to a worthy discussion! The sword of Goujian is one of the most mesmerizing blades I've ever seen. It's unreal how a sword can still look so beautiful after 2,500 years. Maybe it was thanks to the human sacrifice, haha. With that said, welcome to the forum! I think this site really needs people with a passion towards the "niche" aspects of swords: nerds who can delve into questions about swords within a cultural, historical, and technological context. Especially since MyArmoury has seen better days. I'm no metalsmith, but I love reading the ponderings of experts/hobbyists in their field of interest. Historical construction, fashion trends, martial techniques, cultural exchange, all of these are why I find swords wonderful. Perhaps one day this thread helps someone make a perfect recreation of the sword of Goujian. (My budget is $3k, thanks in advance  ) |

|

|

|

Post by larason2 on Aug 8, 2024 9:47:30 GMT

Yes, clay molds were used in the bronze age, but they're hard to make and use. You need a mixture of clay, sand and a binder like straw. the mold is made, and then it's fired like a pot. When the mold is at the same temperature as the copper and tin, the metal is poured in, and they're allowed to cool together. Cool, but a lot of extra work. Still, we know the Chinese smiths used sand molds, and carved them.

Part of what we discussed above is differential casting (casting one thing, then another on top of it), and the differential settling out of tin. There were chinese swords that were differentially cast, but they came after the sword of Guojian. When you cast bronze, the tin naturally accumulates more in the surface and edge as it cools. This was a misunderstanding I had too.

Bronze swords have to be hardened differently than steel swords. Specifically, they are usually work hardened by hammering a groove into the edge. However, the sword of guojian appears to just have been sharpened. The high tin content in the edge helps to harden it without needing work hardening. It's possible they hardened by beating flat, but with the high tin it would already have been pretty brittle. Bronze is different than steel, by casting it, it is already relatively annealed, and it's possible the surface treatment helped with the hardening of the edge.

It's usual when bronze casting to heat it a bit above just the melting temperature, as at melting temperature the metal is still pretty viscous, and you tend to get casting defects. Copper can heat a lot between melting and boiling, so you have a good range to work with.

|

|

|

|

Post by mrstabby on Aug 8, 2024 9:59:39 GMT

This thread gets a lot of resurrectiion scrolls shoved at it lately, I'm not mad though.  The Aluminum depends on the content, because reducing it from Bauxite requires a lot of energy, not that it couldn't be the source, but it would be in the parts per million. I would imaggine most impurities come from the source of their copper.

You can get pretty tight casts, but you always need to shape the result a bit. I am not that familiar with clay molds, I think you could do it with 2 parts but the result will be better when you use one and break it. If they used clay they likely would keep a negative for casting positive wax models for making the molds, with sand they would just keep a positive made of wood for example and impression that into sand. Sand would need more fiinnishing. If the Aluminium comes from the mold it would only be relatively surface level.

I bet it would be better to let the core cool somewhat before you cast the outer layers since the whole thing contracts while cooling, so the less the inner core contracts, the more the outer edges will grab on. They would very likely also have compacted the edge over the core with a hammer to make the fit as tight as possible. That's what it looks to me, a dovetail joint of sorts, I imagine they would do it like this.

|

|

|

|

Post by larason2 on Aug 8, 2024 12:05:05 GMT

Yeah, from what I read the clay mold was one piece. The had a positive, they wrapped the clay around it, then when it hardened they broke the mold off. Then, they put more clay around it. They let that harden, then they fired it like a pot. Quite clever actually.

The later Chinese differential casting had a triangular joint inside, just as you suggest. The sword of guojian was one piece though. The aluminum was probably from something in what they treated the surface with, either lining the mold with it or treating afterwards. There's a bit of iron in it too, so probably some powdered rock. Mostly they were going for sulfur though.

|

|