A French AN XI Light Cavalry troopers sabre.

Feb 22, 2020 13:13:04 GMT

Post by Uhlan on Feb 22, 2020 13:13:04 GMT

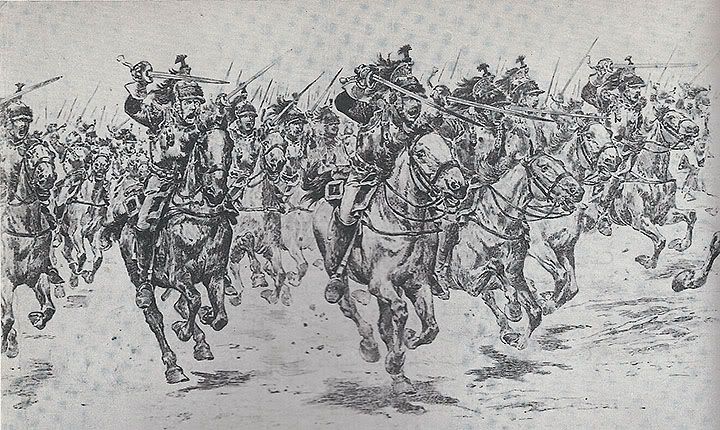

Paris 1814. Last stand at the Port de Clichy.

Introduction.

In this post I really would like to concentrate on the AN IX and AN XI LC sabres and leave the hype and ,,iconic's'' behind.

I gathered some information, some statistics and various other tidbits and some nice PDF's in the notes, in order for you to get a basic grip on the models.

I hope that this post may be of some service when one of you wants to go out and buy one.

Some notes on the French AN IX and AN XI Light Cavalry sabres.

According to the Royal Armoury London:

Development.

The Year IX Light Cavalry sabre was the first French sword intended for use by all regular light cavalry regiments: Hussards, Chasseurs à cheval, Lanciers de la Ligne.and Mounted Artillery.

At the time of its design - the ninth year (AN IX) of the Revolutionary calendar (1800) - France's state of almost constant war demanded a rationalization of weapon production.

Prior to 1800, the two types of French light cavalry had their own pattern of sword. Hussars carried a traditional stirrup-hilted, broad-bladed hussar sabre, of the type used by hussar regiments all over mainland Europe. The Chasseurs à Cheval, befitting their conversion from dragoons, carried a straighter, narrower and longer-bladed sword, with a half basket made up of flattened bars of diamond pattern.

The new sword combined elements of two of its predecessors, retaining the general blade form of the hussar sabre, but having the increased hand protection offered by the Chasseur model. However, far from simply marrying these elements together, the Year IX had a new type of hilt, comprised of three rounded brass bars that provided protection to the hand whilst not limiting movement. This type of three-bar hilt design was to become one of the standard hilt forms of the nineteenth century, but the Year IX was one of the first swords to make us of it.

The Year IX was followed closely by the Year XI sword in 1802, which had a much sturdier scabbard. As with the first pattern of Cuirassier's scabbard, the scabbard of the Year IX was found to be too light and prone to damage, meaning the sword could either not be sheathed or could potentially become trapped inside. As such, the scabbard on the Year XI was significantly thicker and heavier, in order to prevent such problems. In response to another issue of weakness found in the Year IX, the Year XI was made with the bars of the guard extending all the way to the head of the backpiece - or 'pommel' - to make a more robust guard. However, both swords were produced and used simultaneously during the period.

Use and Effect

Although intended for all light cavalry and horse artillery, the Year IX/XI was most enthusiastically received by the more numerous regiments of the chasseurs à cheval, whereas hussar regiments were keen to retain the distinctive sabres of their arm. When lancer regiments were added to French army lists in 1811 they too were armed with the Year IX/XI, and unlike the lance, which was only carried by half a squadrons number, the Year IX/XI was carried by all the regiment's personnel.

Despite the curved, hatchet-pointed blade design it seems that French light cavalry favoured the thrust over the cut. Antoine de Brack, a veteran of the Napoleonic wars as an officer of both the hussars and lancers, remarked that with the Year IX/XI a cavalryman should 'thrust, thrust as often as you can,' because 'the thrust kills, the cut only wounds'. Indeed it was with a thrust that Gudinet, of the 10th Hussars, killed Prince Louis of Prussia at Jena in 1806, after receiving a cut to the face.

Author

Henry Yallop.

Reading the above, especially the ,,thrust,thrust'' part, one would imagine the sabre to be an easy thruster. It isn't. Like with many a sabre the curved blade takes the thrusting tip up and out of line with the grip. My trouble with the later M1822 comes to mind here, where the much longer blade enhances this problem. As a consequence one has to aim under the target to get the tip where one wants it to go.

Many a trooper equipped with the AN IX or AN XI sabre, training be damned, took it upon themselves to file the tip down to clipped point in an effort to bring the tip more in line with the grip.

And I must say, fiddling around with this example, which has a clipped point, it really works too.

Another reason troopers filed on clipped points was that quite often the thin tips broke off.

The sabre under review here has an 86.5 cm blade, while the scabbard can hold an 88 cm blade.

Whether the tip of this sabre broke off or the trooper just did some customizing is hard to tell.

What I could see however is that, in this instance at least, the job was done professionally, with even strokes of a fine file, resulting in a clipped point job with a razor sharp false edge and good and strong lines.

Here are some images of spine signatures:

And some images of the rather crude looking peens.

From what I have seen it doesn't matter whether the sabre was revised or not:

Some images of differences between makes.

For more information you will have to download the PDF's in the notes.

The poinçons.

K under star: Krantz. Director.

B surrounded by laurel wrath: Bick. Inspector. Changed to this poinçon in the beginning of 1812.

L in oval: Lobstein. Inspector of revision.

The first time we see Krantz as Director is in the period March 1812-to begin 1813.

The second time starts in the last months of 1815.

As the blade is dated June 1814 we must conclude the blade was made under the direction of Krantz and inspected by Bick in the 1812-1813 period, which makes the sabre Napoleonic.

Image courtesy of Klingenthal.

In light of the above it may be suggested that the sabre was damaged at some point between 1812/13-14 during one of the many battles at the end of Empire, taken in, repaired in 1814 under the Restoration and probably served again during the Hundred Days and Waterloo.

It looks like the old Manufacture Imperiale etch was (partially?) removed and replaced by the Manufacture Royale etch. There are faint traces of filing on the spine that end right at the J of Juin 1814 part of the new etch.

I cannot see any damage to the blade. There is no evidence of forge welding. The sabre was however taken apart and re hilted. There are the small L and B stamps on the pommel cap, evidence that the new peen was inspected by Lobstein and Bisch.

There is also a small stamp of Bisch as inspector second class on the guard.

Again, there is no evidence of repairs on the hilt.

The basket was approved by Krantz and Bick:

so we may assume that the blade and the hilt belong together.

The numbers.

LOA: 104.5 cm.

LS: 99.5 cm.

BL: 86.5 cm.

BW: 36.5 mm.

BL. Th.: 11 - 6.5 - 6+ - 5 - 2.5 mm.

WOA: 2088 grams.

WS: 1100 grams.

WSc: 988 grams.

POB: 14 cm from the guard.

Work.

As you can see here the blade was quite black, but luckily the rust was superficial for the most part. There still is some small pitting present here and there. The scabbard had some rust too and here too I left the most persistent pits be.

Overall the sabre is serviceable again, with the polish right up to what it should be, while the remaining evidence of age is left in tact.

The little screw in the spine side of the scabbard is there to press down on the spine of the blade in order to keep it locked down in the scabbard. Not all AN's have them but many do.

Conclusion.

Personal, as in biased. To begin with I am not very enamoured by French regulation designs in general.

I love the Bavarian M1826, the Prussian M1811, the Italian M1860, in short, the large and heavy bruisers.

Not the, on average, badly made and rather flimsy British P1796 LC for that matter.

Keep this in mind when you evaluate what I am going to say next.

For those of you who are under the impression, what with all the hype, movies and other propaganda, that these two French Light Cavalry models are some kind of light sabres with mystical and mysterious properties, you'll be in for a great disappointment.

If I had to rate them, they would fall to second place, after the French M1829 Artillery sabre, still my all time favourite of the French regulation sabre line.

To me, the AN's are better than the M1822 for sure. But that doesn't take much.

If we go back in time and look at what contemporaries thought of them, we could say that they were thought to be better than the Prussian M1808, as certain segments of the Prussian Cavalry ditched their M1808's in favour of confiscated AN's whenever they had the chance and refused to let them go to about 1852 when the M1852 came on the market, Blucher be damned.

And the same trend may be observed in France, where it is well documented that many a Cavalry trooper too refused to let go of his or Dads AN IX or AN XI and the sabres also served to about 1855 and if my information is correct, the sabres continued to be made long after the introduction of the M1822.

All this may lead us to believe, even when we take out the propaganda part of these stories,

that the two AN models were much appreciated at the time when compared with contemporary models.

But that does not make them good sabres. This is only evidence that the rest was thought of as worse.

At least in the minds of some.

For me they are mediocre at best. When all the hype and Technicolour is stripped away what you'll be left with is a sabre that's reasonably reliable, not too (nose) heavy, with good reach, a good and effective tool, good value. Dependable, rather dull and not very exciting. Like someone working in the banking sector.

No more, no less.

Cheers.

Mon Dieu et Merde! The Beast is at Waterloo!

Notes.

About the use of the sabre in the Army of Napoleon. PDF: www.researchgate.net/publication/303239451_The_use_of_the_saber_in_the_army_of_Napoleon

Napoleonic Swords and Sabers Collection: AN XI Light Cavalry Trooper's Sword Napoleon Army:

swordscollection.blogspot.com/2012/02/xi-light-cavalry-troopers-sabre.html

Fichier:Grande Armée - 1st Regiment of Chasseurs à Cheval.jpg — Wikipédia:

fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Grande_Arm%C3%A9e_-_1st_Regiment_of_Chasseurs_%C3%A0_Cheval.jpg

Chasseurs à Cheval de la Garde Impériale - Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chasseurs_%C3%A0_Cheval_de_la_Garde_Imp%C3%A9riale

Collection de Sabres et Epées des Guerres Napoléoniennes: Sabre de bataille Officier Chasseur à Cheval Garde Impériale: www.sabresempire.com/2012/01/sabre-dofficier-de-chasseur-cheval-de.html

Unusual french An IX Klingenthal Coulaux freres saber -- myArmoury.com: myarmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.29705.html

Napoleon's Heavy Cavalry, the Cuirassier and Carabinier :: PDF: americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/1997-B76-Napoleon-s-Heavy-Cavalry-the-Cuirassier-.pdf

Nice PDF :: Year IX/XI Light Cavalry sabre - The Battle of Waterloo - Royal Armouries collections:

collections.royalarmouries.org/battle-of-waterloo/arms-and-armour/type/rac-narrative-487.html

Well made propaganda old Hollywood style :: Waterloo :: The incomparable Rod Steiger as Napoleon!

tinyurl.com/yxx5z2h3